Therapeutic life story work in art therapy

Hot topic

In our latest hot topics article looking at developments in art therapy, Katie Wrench talks about life story work in art therapy.

What is therapeutic life story work?

Therapeutic life story work is dyadic therapy in which the child or young person works (usually alongside their adoptive parent, foster carer or special guardian) to develop a coherent narrative account of their history and, with support, begins to make sense of their journey. This means integrating the story so that they can work out what it means for them, how they feel about it and how they might ultimately move towards a more hopeful future.

While most models for life story work focus on exploring the child’s direct lived experiences (Rose, 2012; Wrench and Naylor, 2013; Wrench, 2024; Rees, 2009, 2018) stories in a broader sense are commonly ‘a central resource within therapeutic interventions … designed to provide advice, guidance, wisdom or healing’. Use of metaphor, symbol and ‘themes that mirror but are at a distance from the person … who inspired the story’ can shift children’s understanding of their experiences or help them find a different perspective in a ‘one step removed’ way, which minimises the pain or distress inherent in directly thinking about those experiences (Golding, 2014, p. 21).

Why therapeutic life story work is relevant today

There are increasing numbers of accounts, memoirs and autobiographies written by adult adoptees and adults with care experience highlighting the importance of this work and its relevance today.

Children always have a right to understand why they are not living with their birth parents together with why and how big decisions about their lives and families were made, whatever the circumstances. It is important that we ensure that wherever possible we do not lose any part of the child’s story, and that they can take it with them, wherever they go. They know it already – it is stored in their brains and bodies. By putting words onto these experiences, we are confirming the child’s intrinsic data. By withholding those words or information that would help a child make sense of how they experience the world, we risk increasing their confusion and sense of shame. They may conclude that their story is too awful to bear or to share. ‘They will potentially miss opportunities to safely review events in their lives, come to some understanding and then update their view of themselves and the world.’ (Wrench, 2024, pp. 125–126)

In his memoir, Alan Jenkins, who lived in a care home with his brother and was later fostered, writes about the emotional impact of missing parts of his story:

I know the who. But when, where and why is harder to tell. I have lived with my lack of an early narrative, found strength in it, trusting my instincts. It has fashioned who and how I am. But it is not enough now. And I’m not sure I understand why’

(Jenkins 2017, p.135).

Therapeutic life story work and art therapy

When art therapists work creatively with children and their families, they begin a conversation. In therapeutic life story work, art therapists are in the unique position of being able to introduce creativity as another language, perhaps where words cannot be found, or feelings and experiences might be too difficult to verbally articulate. This is particularly critical when exploring traumatic events in the child’s early history. For those who have experienced abuse or who may have been silenced by the perpetrator, it can be a way of ‘telling’ their story more safely.

As a sensory approach, using art materials in art therapy also allows individuals to experience themselves and communicate on multiple levels: visual, tactile, kinaesthetic etc. With a tangible end product, children can not only be heard but also be seen. The sensory aspects of art making also seem to ‘help with regulation, calming both the mind and the body which is crucial for maintaining traumatised individuals within the window of tolerance’ (Wrench, 2018).

How this approach can help

Mary Carter, a care-experienced social worker, explains what would have helped her while moving through the care system:

I needed to hear my story, have those gaps filled. I wanted to be heard, and I needed someone to remind me of the good things that I had forgotten, rather than all the things that went wrong. How was I able to explore the meaning of these events? When I moved on to new families throughout my teenage years, I could have moved with a clearer sense of my world – in a place in which important decisions were made with care and with a more coherent narrative of my own life.

Mary Carter, care-experienced senior social worker. (Wrench, 2024, pp.14-15)

When children are offered art materials in art therapy, what often emerges is a richer representation of the child’s world than they might be able to articulate verbally. My model for life story practice (Wrench, 2024), which includes three stages, offers a broader understanding of the work as follows.

Stage one is about first consolidating attachment security and supporting children to feel safe enough in their brains, bodies and relationships to go back and think about their early history without becoming retraumatised or overwhelmed by it.

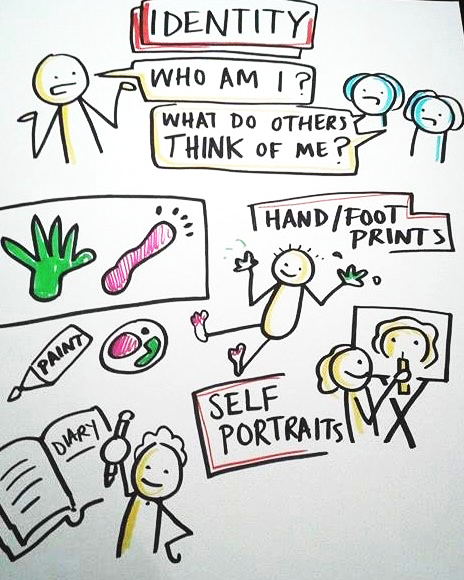

Stage two focuses on building a sense of connectedness, belonging and identity and celebrates the child’s strengths, positive relationships and achievements. This is because children with care experience ‘will not have had the same opportunities to develop positive internal cheerleaders or a chain of built-in memories of people who were there for them – unconditionally and consistently rooting for them, believing in them and supporting them.’ (Treisman, 2017, p. 171).

Stage 3 of the work involves information sharing and supporting children to integrate their story. Many share the belief that the resolution of early traumatic experiences requires a child to have developed a coherent narrative account of their story (Hughes, 2003; Perry and Hambrick, 2000; Solomon and Siegel, 2003; van der Kolk, 2005). Art therapists have an important role to play in this given that ‘traumatic memories are stored as associated feelings and sensory experiences that are not accessible through language alone.’ (Wrench, 2024, p. 122)

Learn more in our upcoming course with Katie

Learn how to use therapeutic life story work in your therapy practice in our upcoming course with Katie. The course is for qualified and trainee therapists already working with children who have experienced developmental trauma.

References

- Golding, K.S. (2014) Using Stories to Build Bridges with Traumatized Children. Jessica Kingsley Publishers

- Hughes, D. (2003) ‘Psychological interventions for the spectrum of attachment disorders and intrafamilial trauma.’ Attachment and Human Development, 5 (3), 271–277.

- Jenkins, A. (2017) Plot 29: A Memoir. HarperCollins Publishers.

- NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) (2021). Looked-after children and young people. Guidance.

Perry, B., and Hambrick, E. (2000) ‘The neurosequential model of therapeutics’, - Reclaiming Children and Youth, 17 (3), 38–43.

- Rees, J. (2009) Life Story Books For Adopted Children: A Family Friendly Approach. Jessica Kingsley Publishers

- Rees, J. (2018) Life Story Work with Children Who are Fostered or Adopted: Using Diverse Techniques in a Coordinated Approach. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Rose, R. (2012) Life Story Work with Traumatized Children. A Model for Practice. Jessica Kingsley Publishers

- Solomon, M. and Siegel, D. (eds). (2003) Healing Trauma: Attachment, Mind, Body and Brain. W.W. Norton & Co.

- Treisman, K. (2017)A Therapeutic Treasure Box for Working with Children and Adolescents with Developmental Trauma: Creative Techniques and Activities. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- van der Kolk, B. (2005) ‘Developmental trauma disorder: Toward a rational diagnosis for children with complex trauma histories’, Psychiatric Annals, 35 (5), 401–408.

- van der Kolk, B. (2015) The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Penguin Books.

- Wrench, K. (2018) Creative Ideas for Assessing Vulnerable Children and Families. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Wrench, K. (2024) Skills and Knowledge for Life Story Work with Children and Adolescents. Jessica Kingsley Publishers .

- Wrench, K. & Naylor, L. (2013) Life Story Work with Children who are Fostered or Adopted. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Additional reading

- Burnell, A., and Vaughan, J. (2017) ‘Beyond words: Family futures’ neuro- psychological psychotherapy approach to the assessment and treatment of traumatized children’, in Hasler, J., and Hendry, A. (eds), Creative Therapies for Complex Trauma: Helping Children and Families in Foster Care, Kinship Care or Adoption. Jessica Kingsley Publishers

- DfE (Department for Education) (2013). Statutory Guidance on Adoption: For Local Authorities, Voluntary Adoption Agencies and Adoption Support Agencies.

- NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) (2013). Looked-After Children and Young People. Quality standard 31 (QS31).

- Ryan, T., and Walker, R. (2016) Life Story Work: Why, What, How and When. CoramBAAF.