UnBoxed: Stories from Survivors of Domestic Abuse

i

i

Kim Bryan (MA , Art Psychotherapist) and Sarah Soo Hon (MA ATR, Art Therapist)

Domestic abuse negatively affects the lives of everyone who experiences it, witnesses it, or becomes aware of it (Callaghan, Alexander, Sixsmith & Fellin, 2018; Mills, Hill & Johnson, 2018). It is not only an individual issue but a societal issue, as it ‘affects society negatively, causing fear among those close to it, and a sense of helplessness among those who are unsure as to what needs to be done to reduce its incidence’ (Rawlins, 2000). As such, domestic abuse can be considered a critical public health issue that requires a thoughtful and inclusive solution (Rakovec-Felser, 2014).

In art therapy, survivors can feel empowered through sharing their stories and engaging with the art process (Murray, Spencer, Stickl & Crowe 2017). Since domestic abuse can have a lasting impact on a person’s mental health (Callaghan, Alexander, Sixsmith & Fellin, 2018; Mills, Hill & Johnson, 2018; Zahnd, Aydin, Grant & Holtby, 2011), art therapy can help to offer support to survivors, witnesses and exposed persons (Allen & Wozniak, 2010; Mills & Kellington, 2012). Furthermore, its practice can encourage engagement with the wider society, in order to deepen understanding of the far-reaching impact of domestic abuse (Murray, Spencer, Stickl & Crowe 2017). In this instance, the exhibition of survivor artwork played an integral role in highlighting the prevalence of domestic abuse in Trinidad and Tobago, while also stimulating solution-focused discussion.

What is Un.Boxed?

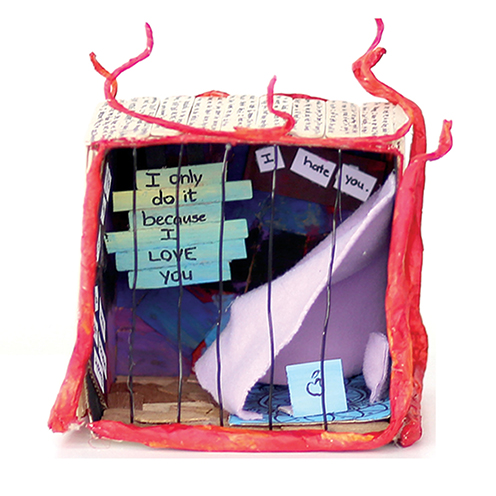

There is inherent symbolic value in a box. It contains, protects, and preserves its contents. In Greek mythology, Pandora’s box signifies the containment of curses and ill fate, which are unleashed once opened. In art therapy, boxes can provide a safe and protective space for holding deeply emotional and traumatic experiences, as well as opportunities to explore the unification of dialectic themes (Farrell-Kirk, 2001). The symbolism of boxes and the containment they provide, is what inspired the project Un.Boxed.

Un.Boxed was an interactive art therapy workshop and exhibition, which explored the impact of domestic abuse from the perspective of the survivor, the reflection of the therapist and the response of the viewer. The exhibition culminated a three-day art therapy workshop facilitated by Kim Bryan and Sian MacLean, who are both practitioners in Trinidad and members on the executive of the Art Therapy Association of Trinidad and Tobago. It was held at the Medulla Art Gallery in Port-of-Spain, Trinidad from 5th – 23rd June 2018.

This project invited survivors of domestic abuse to reflect on the box as a self-symbol in order to explore their internal and external emotions and experiences. Through therapeutic support and reflexivity, they were encouraged to creatively transform their box using a variety of materials. The box could be multi-dimensional, representing many aspects of abuse, a particular aspect of their experience, or even a safe space for protection and containment. The goals of this project were to facilitate the sharing of personal stories; raise awareness; stimulate public dialogue; and provide practical resources for support and healing.

Title ‘Twinkle’

Title ‘Twinkle’

“Un.Boxed was what seemed to be a simple process that surprised me as a survivor. I had to face the fact that although years had passed since I believed myself free….. I was nowhere near recovery. That I would need to commit myself to therapy long term to lift myself out of the hole my abuser dug me deep into. I’m grateful for the entire process and hope many others will consider art therapy to get their stories out instead of being further chained to their past abuse.”

Recruitment

Participants of Un.Boxed were recruited through referral from mental health professionals and other individuals familiar with the project. Volunteering survivors of domestic abuse were each interviewed by the facilitators before being included in workshops and the exhibition. Suitability for participation considered the person’s resilience and access to therapeutic support, including past or present involvement in therapy. Safety concerns were also addressed in relation to the person’s current risk of exposure to abusive situations.

Given the inclusive nature of the workshops, participants were encouraged to provide feedback on their level of comfort with creating alongside both men and women. This was particularly addressed, since the facilitators were aware that it might be possible to trigger traumatic responses, through the presence of the other.

Through discussion, confidentiality and anonymity were identified as key issues by many participants who were concerned about any potential for others to know them, and/or their past abusers. They were each encouraged to maintain group confidentiality during the project.

Once participants completed the interview and felt comfortable with the scope of the project, they completed consent forms. In all, ten participants, including one male, agreed to join the project. The range of participants included a diverse cross-section of persons with differing socio-economic backgrounds and ages (18 – 60 years old).

Title ‘Caribbean Man?’

Title ‘Caribbean Man?’

“This type of pain as a guy sometimes is very difficult to express openly, it’s typically not something males are expected to be vocal about. Making myself this vulnerable and open was in a way freeing, like I found parts of my life and at the same time realise that there is still real pain and issues still within me that I might spend a long time working through. The experience provided me with a little more courage, self-acceptance and hope.”

Workshop

Workshops were held on three consecutive Sunday afternoons. In the beginning, participants were introduced to each other, as well as briefed on the group rules and structure of the workshops. All ten participants attended on the first day. They were provided with a wide range of art materials and found objects in order to create their boxes. Facilitators were present to provide support throughout the process.

By the second workshop, one participant was no longer able to attend. The other nine continued, and were able to complete all three days. However, times for attendance were sporadic and participants experienced difficulty with completing their boxes in the allocated time. As a result, the facilitators offered the option of taking home the boxes or meeting individually to complete them.

At the end, most participants reported that the workshops were helpful with identifying areas of personal difficulty and supporting the way they processed their trauma. Many also felt they became even more aware of their need to access further support.

The workshops seemed to afford participants the opportunity to use art to reflect on their experiences of abuse, and to think about ways in which they felt impacted. Although the project emphasized that the workshops were not a form of therapy, facilitators noticed that many participants required therapeutic support to help them cope with difficult feelings. As participants created, it was evident to the facilitators that some appeared to be overwhelmed by the poignancy of their emotions. Even though many of them were reserved and tended to work in silence, they approached the facilitators for support when they felt inclined. A few of the participants also reported that it was difficult to create in the workshops, and instead used the time to process their trauma with the facilitators. These participants allocated time away from the workshop to create and complete their boxes.

Title ‘Untitled’

Title ‘Untitled’

“Doing this project made me tap into feelings that I realised I had boxed in, to keep myself safe and functional to the public. I remember feeling I couldn’t continue because I had to “unbox” past hurt that I thought I had dealt with. I realised I’m pretty good at burying my hurt till I forget it’s there and then a small trigger turns me into a storm cloud which means I’d be in a bad mood, feel depressed, cry, cuss, get angry or scream. Secondly, I learnt that there was a lot of “ME” I did not deal with and I had to spend more time with me, and rediscover myself in order to heal properly.”

Exhibition

The completed boxes were displayed for three weeks at the Medulla Art Gallery, during which viewers could leave small pieces of response artwork. The exhibition also featured a panel discussion with clinicians, lawyers and speakers from other disciplines, who addressed various topics related to the issue of domestic abuse. Panel members and viewers shared with the facilitators about the relevance and thought-provoking nature of the exhibition. Many also shared that viewing the boxes was an emotional experience.

Participants in the workshops were invited to attend the exhibition and panel discussion anonymously, at their discretion. While some attended, the majority chose not to be present. At the end of the exhibition, very few participants returned to discuss the disposal of their boxes, even though it was addressed at the beginning of the project. When the facilitators communicated with participants about this, many of them seemed keen to forget. One participant even expressed a desire to keep the box, without having to look at it, because of the feelings that it evoked.

Reflection

It is the opinion of the facilitators that the Un.Boxed project enabled domestic abuse survivors to discover more about themselves through a safe, non-judgmental and inclusive space. Participants were able to be vulnerable and honest about their trauma in a space that acknowledged, respected and contained them. In addition, it empowered them to delve deeper into their journey towards self-healing, and encouraged them to seek further support.

The facilitators also felt the project provided insight into the nature of domestic abuse, and the emotional dilemmas that survivors continue to experience. Acknowledgement of of participants’ willingness to engage in this difficult process, being present and attentive to their needs, and helping to support them through the challenging task of discussing disposal, was an impactful experience. This reflective journey through art-making and visual storytelling connected participants, facilitators and viewers in ways that seemed to leave an indelible mark on all.

Title ‘Disconnect’

Title ‘Disconnect’

Title ‘In a garden once grew’

Title ‘In a garden once grew’

References

Callaghan, J. E., Alexander, J. H., Sixsmith, J., & Fellin, L. C. (2018). Beyond “Witnessing”: Children’s Experiences of Coercive Control in Domestic Violence and Abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence,33(10), 1551-1581.

Farrell-Kirk, R. (2001). Secrets, Symbols, Synthesis, and Safety: The Role of Boxes in Art Therapy. American Journal of Art Therapy,39, 88-92.

Mills, C. P., Hill, H. M., & Johnson, J. A. (2018). Mediated Effects of Coping on Mental Health Outcomes of African American Women Exposed to Physical and Psychological Abuse. Violence Against Women,24(2), 186-206.

Mills, E., & Kellington, S. (2012). Using group art therapy to address the shame and silencing surrounding children’s experiences of witnessing domestic violence. International Journal of Art Therapy,17(1), 3-12. doi:10.1080/17454832.2011.639788

Murray, C. E., Moore Spencer, K., Stickl, J., & Crowe, A. (2017). See the Triumph Healing Arts Workshops for Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence and Sexual Assault. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health,12(2), 192-202. doi:10.1080/15401383.2016.1238791

Neuman Allen, K., & Wozniak, D. F. (2010). The Language of Healing: Women’s Voices in Healing and Recovering From Domestic Violence. Social Work in Mental Health,9(1), 37-55. doi:10.1080/15332985.2010.494540

Rakovec-Felser, Z. (2014). Domestic violence and abuse in intimate relationship from public health perspective. Health Psychology Research,2(1821), 62-67. doi:10.408/hpr.2014.1821

Rawlins, J. (2000). Domestic Violence in Trinidad: A Family and Public Health Problem. Caribbean Journal of Criminology and Social Psychology,5(1&2), 165-180.

Zahnd, E., Aydin, M., Grant, D., & Holtby, S. (2011, August 30). The Link Between Intimate Partner Violence, Substance Abuse and Mental Health in California[Policy Brief]. Https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7w11g8v3.

Photos Courtesy John Francis Jr. @Lime.tt – full gallery available here

This article was first published in Newsbriefing (Winter 2018), a publication for members.

Everyone is welcome to join us as an associate member if they are not an art therapist here