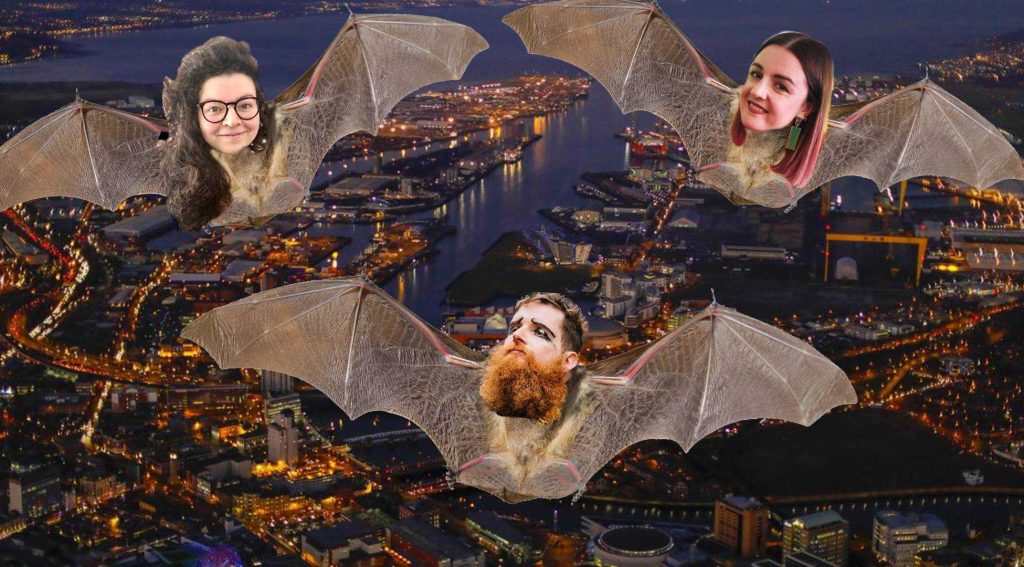

An interview with the Turner Prize winning Array Collective

Reflection

The Array Collective are a group of individual artists rooted in Belfast who explore and discuss socio-political issues affecting communities in Northern Ireland in a fresh and playful way. The collective, which includes art therapist Stephen Millar, won the 2021 Turner Prize for their collaborative actions and art responses to several issues – reproductive rights, gender and language (among others), and the trauma surrounding these.

Stephen Millar and Jane Butler from the collective presented at our Annual Conference in November 2022 themed around art therapy, trauma in society, and social activism. They spoke alongside art therapist Méabh Meir, one of many artists invited to perform at the collective’s Turner Prize-winning event in Belfast – The Druthaib’s Ball. Here we talk to Stephen and Jane about their work and how it relates to art therapy.

Tell us about the Array Collective

Jane: Array is a collective made up of eleven individual artists. We started as a studio to provide affordable studio spaces for artists in Belfast. In 2017, we found ourselves out on the street protesting issues such as women’s bodily autonomy, marriage equality and so much more. That naturally formed the collective.

Could you tell us more about your work as individuals?

Stephen: Among the eleven of us there are photographers, filmmakers, everything. I’m a painter. And in my day job, I’m an art psychotherapist working in primary schools in West Belfast. I’m also a performance artist.

Jane: We’re all involved in many different things – from education to the heritage sector. I have worked with children and arts for different arts organisations in Belfast for many years, but I’m not an art psychotherapist. Within my individual art practice, I am interested in how trauma is held in the body. I make work in response to that.

In 2021, the Array Collective won the Turner Prize. Could you tell us more about your winning piece, The Druthaib’s Ball?

Stephen: 2021 was a significant year in Northern Ireland because it was the centenary of partition. We wanted to do something that would highlight the legacy that partition left us with, issues that we’re still fighting for that affect many people and communities.

We produced a film and invited other artists to contribute. We wanted to speak with people on these issues, not for. Our aim was that other artists, activists and performers would come along and use the Turner as a platform to raise their voices. We held a fantastic night of music and performances at the Black Box, an art community space in the city. Every single attendee came in fancy dress, each responding to the theme of centenary in their own way. Their characters and fancy dress became central to the film.

The night, and then the film itself, ended up being a 40-minute rollercoaster of emotion. It went from the absurd to the very funny to the deeply poignant, and mournful, then up again! It was powerful. And that speaks to collaborative working, bringing other people in and trusting them. And there’s something about trauma-informed practice when you trust others and work collaboratively, the community starts to work with itself.

Jane: We knew we wanted to create a film for the Turner Prize, but the question was how we would show it and how could it hold a space in the gallery. We create a ‘síbín,’ a pub ‘without permission’, filled with symbolic artefacts and objects. From a very basic level, when you enter the síbín, it feels like a familiar comfortable space. It’s a pub, the TV screen is on. After a while, especially sitting with the film, you are confronted with the uncomfortable, which creates a space of tension. The síbín represented a change and a passage of time.

Stephen: We created a space for people to sit with trauma. We knew that the film was heavy. And even the parts that weren’t heavy were still heavy. This space allowed people to sit with all this weight. It’s easier to do that in the pub than in the gallery.

The objects, from paintings to photographs to ceramic objects, also helped create that space. Everything was designed as if you would find it in a pub, but everything had a different meaning, a point of reference, sometimes subtle, sometimes on the nose. People would read the newspaper, but the newspaper wasn’t just a newspaper, the newspaper was also an object. It was there for a reason. Even the ceiling itself was made from a canopy of dozens of banners from different marches: women’s bodily autonomy, LGBT marriage, fighting for the NHS, Irish language, and everything in between. We were literally covered by the cause.

Jane: It was so multi-layered. Every single detail was analysed, but at first glance it just seemed like a regular pub.

Stephen: And there was something about that too. The Irish owning a pub. Owning our old stereotypes. We knew that this was a major exhibition, one of the biggest in the UK and England. And we knew how it would be seen, but if people want to stereotype us, as they often will – here we could give it back.

How do you see the relationship between artistic practice, social activism and art therapy practice?

Stephen: I suppose what we’re interested in is conversation changing, and this is why we spoke at the Annual Conference of the British Association of Art Therapists. Perhaps our presentation won’t ultimately change how people work individually in the clinician’s room, but it’s important to have the conversations, and work collaboratively. And that’s what we do as a collective, we try to bring in and include as many people as possible.

When working with clients, they can be making great progress, but they could be going back to a damaged family or damaged community. If we don’t consider how to work in those contexts as well, then we’re only ever papering over the cracks. What we do might not be specifically defined as ‘art therapy’, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t have a therapeutic benefit. But even inviting people to sit with very difficult issues has a place, and the conversation and safe space gives people permission to play with and consider causes they may be passionate about.

Jane: When we were preparing for the Annual Conference and thinking of ideas around how we work and how those different ways of working can transfer over into art psychotherapy, we explored the idea of storytelling, collaboration and building of communities, which in some ways connect artistic practice, social activism, and art therapy practice.

Stephen: The storytelling aspect is important. We lean heavily on mythology and history to make contemporary stories, and we pull that into our individual and group work, helping clients to consider their own mythological history. We play with different ways of storytelling constantly, and it is important to be open minded!

What are the challenges and the joys of working with trauma as a collective?

Jane: We work a lot with tough issues, and within the group we have a safety net and care for each other. Some of us have been affected by the issues that we are protesting about, and it can be tough, but there’s something about doing it together that feels (without being cliché) like a family.

Stephen: We talk about such heavy issues. It’s all about our trust in each other. Being there for each other. Being a team rather than one individual.

The challenge is being careful we don’t speak for someone else. We speak with, this community, not for it. We all have different ideas and belief systems, and we care passionately about different things. Everyone’s belief system and passion are equal and relevant. We try to be as mindful of this.

How do you see your practice within the collective relating to your work as an art therapist?

Stephen: As an individual, being very publicly performative in terms of street intervention means people know who you are and what you stand for. After we won the Turner Prize, clients and specifically parents of clients became more aware of the issues we were raising as a collective. Some were fine with it, some not so fine. Of course, the work we do outside the art therapy room doesn’t change the fact we have complete and utter focus on the client.

What would you say to art therapists who want to be more involved in social activism? How does an art therapist also be an artist and a social activist?

Stephen: I don’t think there’s a rulebook for any of that. At the Annual Conference we didn’t want to do a Q&A, so we craftily set it up that we didn’t have to. We set participants a challenge to create flash cards for causes they care about. This was a new audience and a new demographic, with different career backgrounds. We wanted to hear what they cared about, and we wanted them to think about what it is they care about. And if there is something you care about – get out and campaign!

Jane: Yeah, the rules of Array are: get out and campaign with local activist groups, be welcoming and hospitable, and have a GEG (the Belfast way of saying ‘have a laugh’). We deal with a lot of tough issues, but it’s important to bring lightness into the work.

Stephen: Our advice for art therapists: find out what it is you’re passionate about. Things won’t change without your involvement. Engage with local groups that are already campaigning. Find your community, they are already around you.

Upcoming exhibition

The Array Collective’s winning piece The Druthaib’s Ball will go on display at the Ulster Museum, Belfast in February 2023.