In our global economy, we are continuously faced with challenges which relate to the integration of cultures and the understanding of different norms throughout diverse societies. One of these challenges is exacerbated by the reality of traumatic migrations. Many people feel forced to flee their homelands due to economic, social and political difficulties, in search of places where they feel safe and may have the potential to build healthy and successful lives.In Trinidad and Tobago over the past two years, there has been an influx of Venezuelan nationals, seeking asylum in an attempt to escape the socio-political turmoil in their country of origin. As a result, Trinidadians and Tobagonians have been forced to adapt to the changing dynamic of their social infrastructure, as more and more persons arrive within the country in search of a better life. Trinidad and Tobago has become a “host community”, the country of asylum with all its local, regional and national governmental, social and economic structures within which these asylum seekers/refugees live.

As art therapists and practitioners working within the dynamic of this globalism, we are faced with the reality of how these challenges impact the work of art therapy and how working with art therapy can support this overall process. Kapitan et al (2011) suggest that ‘art is a transformational act of critical consciousness’ that not only awakens new ways of thinking and learning, but can also create an environment that facilitates change on a macro level within community practice by “engaging a people’s collective dream life, their hopes and images, their histories and their discovery of new ways to go forward” (p.64).

In this context, art therapists can be seen as activists who help to facilitate social transformation through acknowledging and utilizing cross cultural commonalities in a sensitive and reflexive way. This is achieved through embracing awareness of the connection between personal and collective suffering and developing knowledge of the cultural context, while examining personal values and beliefs. Working with a theoretical framework which considers some aspects of human physiological and psychological experience universal, and creativity in all cultures perceived as having the potential to engage and transform pain, we view art therapists as vehicles for advocacy. Although cross cultural commonalities exist, art therapists must remain culturally sensitive and able to engage in critical reflection about the multiple levels of experience within each cultural context. Here, art therapy and social action are linked, not only through the power of the image and its ability to mediate between the individual and the collective, but also its ability to access the different levels of experience of communities through arts-based enquiry.

“when people come together to practice critical inquiry, they develop a capacity to see, reflect and respond to their own situations no matter how difficult those situations may be. Out of this communal process the work of healing and reconciliation inevitably arises” (Glassman, 1998)

The Project

As part of a project to address challenges of integration between the host community in Trinidad and Tobago and Venezuelan migrants, an art therapy project was planned. The goal of the project was to bring these two populations together to begin a dialogue about fostering integration in the national context. The goals of the project were focused on mutual respect, communication, and the ability to openly express fears, hopes and discuss potential strategies for collaboration.

Twenty people, male and female, above the age of eighteen years were selected to participate from both the host community and the Venezuelan community, based on their willingness to engage with conversations around integration. The project focused on the creation of safe spaces together. The workshop, a joint UNICEF and Jabulous (a local NGO) initiative was facilitated by myself, an Art Psychotherapist and a Venezuelan national, Andreina who is trained in psychological first aid, and is a key focal point within the Venezuelan community. Andreina also operates a ‘safe space’ for Venezuelan nationals, where she offers a range of services and activities including childcare, educational support, stick fighting, drumming, parang and other creative activities.

Participation in the project was on a voluntary basis and participants were selected and screened through various methods. The first criteria for participation in the project was that they were over eighteen years of age. In order to support social cohesion, we selected persons from both the Venezuelan community and the Trinidadian community. We focused on Arima, which is a borough within Trinidad and Tobago, and selected a community space and a community leader to work with us to recruit participants from the Venezuelan community.

The Trinidadian participants were selected through the Program Director, based on: age; stakeholder status (worked in key services within the Arima community, such as education, health care etc.); and being open to dialogue about integration. A pre-questionnaire was formulated that was utilized to explore potential participants' feelings regarding the amalgamation of the two cultures, and challenges presented by migration. This was to gauge not only participants' interest in social cohesion, but whether there were attitudes and opinions that may present difficult dynamics within the groupwork. No potential participants were excluded.

The process

To introduce the project, a written brief was distributed to all participants in their respective languages so that informed consent could be gained. On the day of the workshop, persons were split into five groups which were a mixture of both Venezuelan and Trinidadian nationals. The discussion started with the creation of group rules which the group collectively agreed on: no politics; no religion; and mutual respect. It was clear that by formulating these rules some of the key elements which they felt were a hindrance to collaborative working were highlighted. After formulated group rules were finalized, the project was explained in English and Spanish.

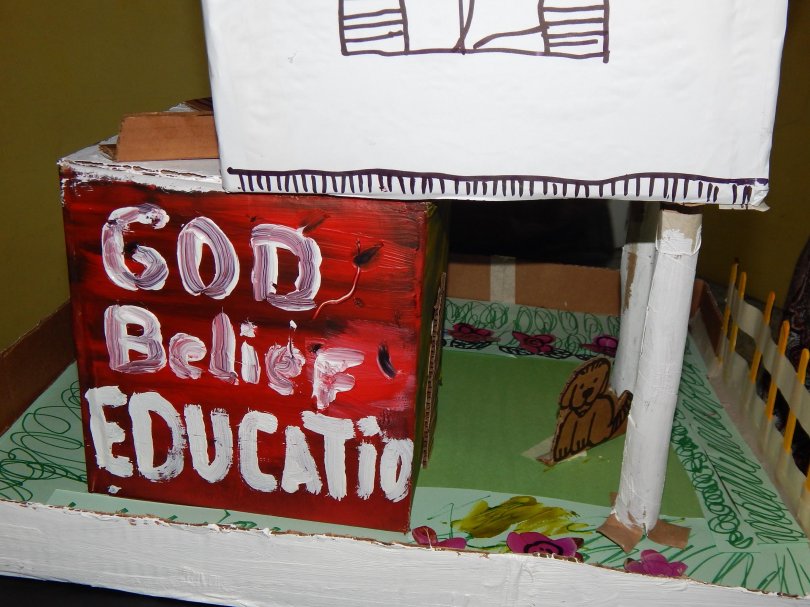

The directive was to use the theme of ‘the box’ to create a “safe space” together. The safe space could be things internal or external which participants believed would support integration within their communities. Participants were encouraged to think about what made them feel safe, and how, within the new landscape of communities, and what things, tangible or otherwise, they would want to support more harmonious livelihoods. There was no specific directive in regard to how the box should be used, however all of the groups chose to make houses as it seemed to indicate that most participants associated safety with “home” or having a home.

Participants were then encouraged to find a space within the facility where their group could work. The five groups each found a space to work and began the process by trying to find ways that they could communicate their various thoughts and ideas to one another.

“I’m an artist and art teacher but this was my first art therapy experience. and with someone whose first language is not English. It’s true what they say though ... art, like other forms of creative expression (music /dance /drama), is a universal language. In quick order and with the help of google translator we devised a plan to create our safe space using a variety of art materials. We focused on feelings, both ours and our Venezuelan counterpart A, and created a house full of uncertainty and anxiety but also one of hope ... which I think is the most important feeling of all. It was an interesting and rewarding experience”

Cross-cultural Art Therapy

Art is a modality which has the potential to facilitate cross-cultural exploration in a way that most talking therapies cannot. As I embarked on this project, language was one of the key considerations. As one of the key goals was integration, I was aware that, by mixing the host community and the Venezuelan community, there would be some deficiencies with regards to language. Many of the Venezuelan nationals did not speak much English, and the Trinidadians spoke little Spanish. As a therapist and co-facilitator of the project, I am not fluent in Spanish, but my co-facilitator was bi-lingual and provided some translation support. In structuring the process, I recognized that the art object had the potential to bridge this gap and to create a focal point whereby they could access collective feelings. McNiff (2009, p.104) states that:

“art objects, materials from nature, rhythmic music and dance, gesture and dramatic enactment has enabled shared communication to take place on a level of mutuality that parallels comparable experiences in situations where a common language exists. The absence of verbal language can actually have positive results, focusing even more energy on the significance of the art object. Body movement, facial expression and the tone of voices are similarly influenced when there is not a shared verbal language. Other forms of communication by necessity begin to compensate for the loss”.

Although most of the participants found the lack of language challenging at first, most groups did not request translation support. Instead, the groups found different ways to compensate for the lack of language. Some of the groups utilized google translate, while others used verbal and non-verbal cues. The groups, as they discovered ways to communicate, also discovered commonalities with each other, and were able to collaborate by sharing their feelings and hopes and creating projects which demonstrated their shared experiences.

Accessing Feelings and Growing Together

One of the factors that became evident in the groups was that there were many shared experiences. In one group, the participants noted that they were all educators, while others recognized that they shared similar values and feelings. Most of the finished projects examined value systems such as education, which would help to support the process of integration. It was through the process of making art together that people were able to recognize their collective beliefs and ideas and share together. There is an increasing body of literature that asserts the effectiveness of art therapy as a tool to support the building of rapport in a non-threatening way, particularly in settings where practitioners must work cross-culturally. Moreover, the creative arts are increasingly becoming utilized to effect change. Artmaking has many social aspects which can be tapped into, and the community becomes a client and partner to work towards social transformation. When communities and art therapists form collaborative partnerships, the potential exists for an intervention which addresses the key demands faced by the community to take place.

Conclusion

In traditional practices of medicine, the creative arts were utilized by healers to impact not only the individual but also to influence social change as a whole. The individual was seen as a part of a microcosm which was society, with their illness having an impact on society on a macro level. Over the last few decades, art therapy, and by extension the creative arts, has re-emerged as a key intervention in the practice of community healing. This purposeful use of the therapeutic and transformative qualities of art interventions is focused towards building communities and creating collaborative partnerships that create the environment for social transformation and emancipation.

Kapitan (2011) states that … “when practiced in the community, in collaboration with community leaders and organizations, creative art therapy may assist not only in bringing people together but also in realizing the true goals of social action, strengthening the capacity of people to discover better ways to meet their needs and impact their reality.” This is exemplified by the utilization of art therapy globally as a social action tool to help communities recover from genocide, mobilize humanitarian action in war-torn countries and to counteract critical distress caused by natural disaster.

Art therapy has a key role to play in the shifting of the paradigms in our global economy. Art therapists are reflexive practitioners who have the potential to bring the individual and community together to promote better health and wellbeing overall, while tackling key social collective consciousness. In the face of our ever-changing global dynamics, as practitioners, community members and community-based organizations, we are challenged to find ways that we can work together for better integrated and successful communities. Art therapy can be an integral part of this process in growing together in these times of change, as we reflect on how we can learn from each other and use culturally sensitive and person-centered approaches to facilitate lasting change.

References

Hocoy, D. (2002) Cross-Cultural Issues in Art Therapy. Art Therapy, 19:4, 141-145, DOI: 10.1080/07421656.2002.10129683

Hocoy, D. (2005) Art Therapy and Social Action: A transpersonal framework. Art Therapy, 22:1, 7-16.

Kapitan, L., Litell, M. & Torres, A. (2011) Creative Art Therapy in a Community's Participatory Research and Social Transformation. Art Therapy, 28:2, 64-73, DOI:

10.1080/07421656.2011.578238

Kapitan, L. (2015) Social Action in Practice: Shifting the Ethnocentric Lens in Cross-Cultural Art Therapy Encounters, Art Therapy, 32:3, 104-111, DOI:

10.1080/07421656.2015.1060403

McNiff, S. (2009) Cross-Cultural Psychotherapy and Art, Art Therapy, 26:3, 100-106, DOI:10.1080/07421656.2009.10129379

Copyright (c) The British Association of Art Therapists (BAAT)

This article is published in BAAT Newsbriefing Summer 2020 and may not be distributed or published without the consent of BAAT