The history of the group

Prior to the COVID-19 global outbreak, we had been running a closed art therapy group for young adults with Learning Difficulties and Disabilities (LDD) and/or physical conditions for almost a year. The group met fortnightly for open group sessions in a studio-setting within a vibrant artist community in London. In the open studio context, the young people are known and referred to as members or artists. The model was primarily influenced by that of The New Art Studio in which members make art within a therapeutic context and relationship, potentially exhibiting their artworks (Martyn, 2019). Our approach aims to offer members a safe, consistent space and a creative outlet, encouraging a sense of purpose. An opportunity for group interaction was established to combat social isolation, even before the pandemic.

Though group sessions are confidential, members are periodically invited to exhibit chosen artworks and exhibitions take place with their verbal consent. Where there is limited capacity, parents/carers may provide consent on their behalf. Similarly, all members have agreed to the publication of their images for the purposes of this article either verbally or through text message. Additional consent has been sought from parents/carers via email and text message. All members remain anonymised throughout this article.

Loss

Many members had experienced or were facing the death of a relative or parent. This was coupled with the loss of education, and thus routine and structure due to their age, potentially leading to reduced sense of agency. Though not intended from the outset, bereavement and loss emerged as pertinent themes within the group. Loss is a universal experience, which can become both practically and emotionally more complex for one who is dependent on another. Furthermore, it is increasingly recognised that those with LDD (particularly thosewith Autistic Spectrum Conditions (ASC)) may find loss difficult to process, consequently becoming ‘stuck’ in a state of grief (Attwood, 2003).

Transitions

Over the course of the year, the group lost and gained members before becoming more consistent with five regular members, two art therapists and a support worker. With the founding art therapist, Gillian, preparing to commence maternity leave in the spring, the group began working towards this ending. This transition took place over a four-month period starting when the pregnancy was first announced to the group. As Skaife (2012) explains, the pregnant therapist can evoke intense and primitive feelings amongst group members and this was acutely felt in the context of this group. It appeared the role of art became evermore important in containing the feelings aroused amongst members(Figure 1).

Figure 1. Artwork made before Gillian went on maternity leave

With this in mind, the sessions preceding Gillian’s maternity leave felt highly emotive. The group was already undergoing a transitional period which coincided with the lead up to the global pandemic and UK-lockdown. With less than a week until the final session before changes were implemented, studio sessions were cancelled to comply with safety measures announced by the government. Parents and caregivers were notified but the art therapists were aware of the intensity and suddenness of this loss for members. It was clear that an alternative means of running the group needed to be sought.

The birth of the online group

Adaptations

After reviewing the emergency guidelines published by BAAT (March 2020), the challenges of providing a suitable alternative for the group felt too great given that the members differed widely in their communication needs and preferences. This generated frustration over a sense that our client group had been overlooked, a common occurrence in many contexts. This now collective sense of frustration perhaps led to the development of a uniquely inclusive online platform where group members could remain united through their creative processes.

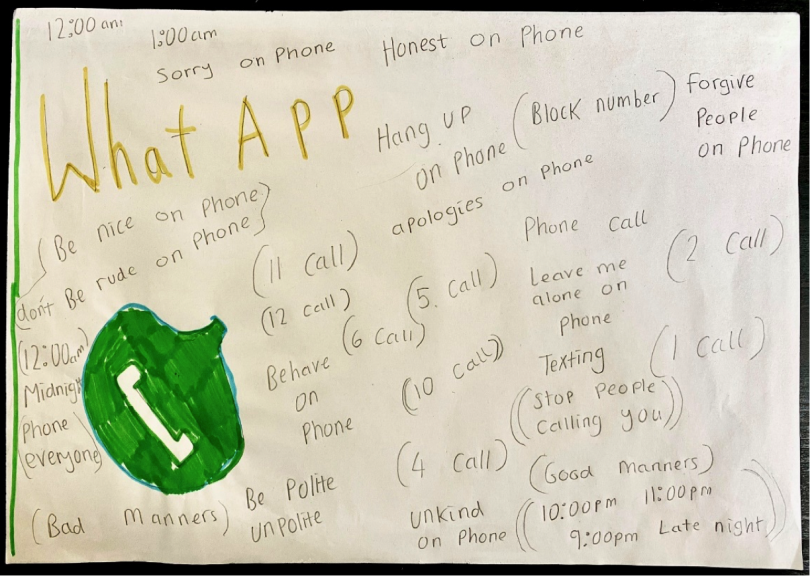

As all group members are young adults, sometimes treated much younger than their years, it felt important to use an online platform which would maximise their sense of independence. After multiple conversations between facilitators, it was decided that the most suitable forum would be WhatsApp. The platform, already utilised by members, was familiar and accessible. Coincidently, it also featured in recent artworks produced in sessions (Figure 2).

Figure 2: WhatsApp Etiquette

Upon seeking consent from members, parents and caregivers, boundaries were set for an online group. Typical session times were extended based on a sense that immediate contact could feel diluted online. Plans were made for how to facilitate the group in this new and unfamiliar context. We were struck by how many methods of communication were available on this platform, including text, sound, image, video and emojis. This felt very inclusive of the different communication needs of the group and potentially suitable in holding the group.

Paralleling face-to-face meetings, the art therapists continued to make art alongside members. Boundaries, such as regular breaks from online interaction, were modelled as well. A main aim was to maintain the fluidity and openness to what may naturally occur aswas established in the studio. It also felt necessary to arrange multi-way telephone or video calls with each member, allowing facilitators to have some interaction with individuals. It was hoped these ‘holding sessions' would allow the safe containment of Gillian’s absence and assist in the transition toward the remaining art therapist and support worker taking over as main facilitators.

Materials

Whilst members would potentially have access to some form of art materials, it felt important not to make assumptions, presenting the issue of how materials could be safely distributed. Time limitations, restricted movements and a looming reminder of a duty in preventing the spread of COVID-19 meant careful consideration was necessary. Ordering new materials online was perhaps the sole recourse. The option of providing a pack of basic materials to ensure consistency was originally considered. However, it was finally agreed to select materials with a personalised approach, demonstrating attuned insight into the preferences of each member. All members received a sketchbook and two options of media, including a material fundamental to their process already started in the face-to-face sessions. The offering of ‘more’ seemed to resonate with decision to offer extended online provision. This may reflect a collective sentiment that online communication does not provide the same extent of interaction as physical presence.

Going online

Prior to the first online session, there was a shared sense of excitement between us, the art therapists, the support worker, and members alike. This was evident in the amount of activity taking place outside of the session hours. The appeal of a creative space may have presented some respite from the surreal circumstances. Our new found isolation possibly heightened our sensitivity to the isolation faced by some members and thus the importance of the group in their lives. There appeared to be synchronicities between the original aims of the group and our move online: creative interaction and a way to feel connected.

As the group opened online, the usual greetings were made; all members were ‘present’ and shared images of their art materials. The boundaries were shared in various formats, including text, audio recordings and video, in attempt to reach all members. Everyone was reminded of this session marking a beginning and an ending before Gillian began her maternity leave. It seemed that the use of emojis or stickers was really important, enabling group members to express emotions more easily:

Within conversation about COVID-19

Within conversation about Gillian’s leave

There was a flurry of art making, with several images being shared, increasing the feeling of connectedness. This illustrated ways in which WhatsApp may provide a comfortable medium for expressing difficult emotions by this generation and particular client group.

Roles and control

Paralleling the group culture already established, distinct roles were adopted and apparent in the online group. However, it seemed this new means of interacting encouraged more openness around the expression of identity in some members, particularly where verbal interaction is a challenge. A change in how members related and engaged with the group as a whole was observed more noticeably on this platform. Additionally, it was evident that more reliance was placed on the group and less on individual facilitators.

For us, hosting an online platform on WhatsApp generated uncomfortable feelings around control and, at times, felt invasive of group members’ social space. After the first online session, we decided to temporarily close the group by removing members and re-adding them before the next session. Unfortunately, there was no other way to deactivate and re-activate the group on WhatsApp. For the art therapists, this initially felt both controlling and harshly rejecting. However, it proved to be an effective way of maintaining the boundaries and containing the interactions to within the session time. Members nonetheless continued to comfortably engage with the online platform.

Themes from the online group

Virus

Prominent themes to emerge in sessions include separation, anxiety around uncertainty or endings, birth, and death. Whilst these would be anticipated given Gillian’s departure alongside other impending losses, this ultimately took on a different form due to the pandemic.

We observed several images which we perceived as representations of the COVID-19 virus (Figures 3 shows an example). These images may have served as a way to imagine the invisible, deadly virus.

Figures 3. Images which appear to resemble the COVID-19 virus

Individual ‘holding sessions’ via text, telephone or video call were also helpful in identifying confusion around Gillian’s leave being related to illness rather than pregnancy. Though it was explained that the leave would be temporary due to having a baby, it seemed there was a merging of her pregnancy with the virus, causing much upset over her wellbeing. In this case, holding one-to-one sessions alongside the group proved essential in containing such concerns, ultimately allowing a good enough ending to take place.

Food

We also perceived other prominent themes including: comfort, commodity and nourishment represented by artworks featuring food items (see example, Figure 4). These images may also relate to the shortages of some essential supplies during the beginning of UK-lockdown due topanic buying.

Figure 4. Ice cream, pizza, pancakes

Separation

Following Gillian’s departure, members visually and verbally expressed missing her. Flowers, expressive faces and hearts were drawn “for” Gillian in her absence. This overlapped with other aspects which members missed about life prior to the pandemic, such as: physical contact with others; cultural, religious, and personal practices; and celebrations which could not be experienced in the same way during lockdown (see examples, Figure 5). Using the WhatsApp platform enabled members to have these feelings and losses acknowledged, often resonating with each other.

Figure 5. Tapestry of things missed during lockdown: ‘Friendship’, ‘Fireworks’, ‘Hair Salon’, “Bus Going to the Shops”, ‘Gillian’ and ‘Golf’

Independence

Another noticeable theme to emerge, particularly after Gillian’s departure, has been the theme of independence. With some members due to leave education on 3 July, anxieties may have been stirred over whether the celebration of this ending can now take place, or not. Nonetheless, a sense of excitement in relation to independence and freedom had been part of the group before lockdown. One member wished the others a ‘Happy 4th of July’ some two months early, whilst creating images of fireworks. The paradox members faced in their imminent ‘independence’, whilst currently experiencing lockdown, could have been confusing. It may be that members were able to use the group to metaphorically mark and celebrate their upcoming independence through artistic processes, as well as their desire to be free of the virus as exemplified in Figure 5.

The future of the group

Challenges

The facilitation and culture of the group continued to be influenced and shaped by challenges encountered along the way. With facilitators being contacted more frequently between sessions, we shared concerns over whether this could lead to feelings of resentment, conscious or otherwise, if continued long-term. It is difficult to know whether increased contact is related to the move online or due to anxieties caused by the pandemic. Likely to be both, the stance taken has been to redirect individuals back to the group where possible in order that they access a collective problem-solving and support network. However, for those with acute anxiety and/or ASC, there is an element of repetition to their communication which must also be taken into account. Whilst it is not possible to respond to every attempt at direct communication, we have to think carefully about how to manage feelings of rejection. We have used supervision to further explore these complexities and ethics.

Parental Participation

Whilst itis a closed online group, some family members naturally became more involved in the art making processes, co-creating works or completing their own pieces. Whilst this was felt to be beneficial, particularly in the parents’ willingness to connect and experience the value of the group first-hand, this raises questions over confidentiality. It may also reduce members’ sense of agency and autonomy as adults. However, parental participation was essential for a particular member whom could not access WhatsApp without support. Though this felt natural and the attempt at inclusivity appeared to be accepted within the group, such changing boundaries may have impacted on experiences of personal space and privacy. We will explore these issues with the young people, both online and when the group return to the studio. In this respect, it is vital that adequate space is allowed for such feelings to be expressed retrospectively within the therapeutic relationship.

Economic Issues

With the use of materials not solely limited to studio session times, the rate at which they are used becomes financially problematic albeit a positive sign of ongoing creative expression. Reflecting wider social and political issues, the cost implication is simply unsustainable. Whilst mindful not to overly direct, we now suggest the use of recycled materials, photography or environmental art. In this sense, a focus on environmental factors within the field is possibly overdue and the current circumstances seem to have presented an ideal opportunity to explore resourcefulness to minimise consumption and waste.

Conclusion

The pandemic has forced us to live with uncertainty, with a timeframe of when studio sessions will resume remaining unclear. This continues to be a prominent theme and is challenging for us to hold. However, it seems that WhatsApp has enabled us to offer a group where the difficult realities of the lockdown could be expressed and managed. As illustrated, there are also noticeable benefits to this way of working, particularly with this client group. Although art therapy research is only just beginning in light of the pandemic, evidence that members find this online adaptation acceptable and engaging is demonstrated through their continuous willingness to participate with enthusiasm, colour and excitement.

References

Attwood, T. (2003) Keynote Speech. World Autism Congress, Melbourne Australia.

British Association of Art Therapists (March, 2020) Emergency guideline on managing art therapy practice and looking after clients during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Martyn, J. (2019) Can Exhibiting Art Works from Therapy be Considered a Therapeutic Process?ATOL: Art Therapy OnLine 10 (1).

Skaife, S. (2012) The pregnant art therapist’s Countertransferencein Hogan (Ed) 2012 Revisiting Feminist Approaches to Art Therapy.

Copyright (c) The British Association of Art Therapists (BAAT)

This article is published in BAAT Newsbriefing Summer 2020 and may not be distributed or published without the consent of BAAT