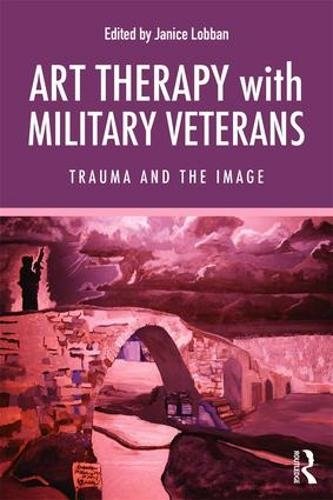

Art therapy with military veterans: trauma and the image, Edited by Janice Lobban, Published by Routledge 2018

This book is a unique collaboration between many professionals working in this field, brought together by the editor, Janice Lobban, who also contributes to seven out of the 14 chapters. The professionals include experts in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), military mental health psychiatrists, research academics, army personnel, artists and art therapists. Many of these have a connection with the organisation Combat Stress, set up to help veterans suffering from PTSD; and for which the editor has worked as an art therapist since 2001. She is now the Senior Art Psychotherapist there, in charge of a team providing a valued service. This book is the outcome of their experience so far.

Another vital element of the book is the contribution of whole chapters and case vignettes by clients of Combat Stress, detailing their experiences and the way that art therapy has helped them. It’s impossible to read some of these accounts without shedding a few tears or at least feeling a lump in one’s throat. Many veterans fail to reintegrate into civilian life because of PTSD, and they are over-represented in prisons and homelessness populations.

The book is in four parts:

- Art therapy and post-traumatic stress disorder

- The British forces

- Current approaches to art therapy with veterans in the UK

- Taking a wider perspective

The first part outlines the history and development of art therapy with military veterans, starting with war artists in World War 1, including John Nash and Adrian Hill, who later coined the term ‘art therapy’. The incidence of ‘shell shock’ in World War 1 has now been recognized as PTSD, and Combat Stress was founded in 1919.

The chapter by an army reservist makes heart-rending reading until his referral to Combat Stress, which helped him recover. The following chapter, on the biological basis of PTSD, is quite hard going but is made more understandable by drawing on the specific example of the previous chapter.

I enjoyed some of the metaphors used about art therapy. One was the reference to art therapists as ‘stealths’, referring to stealth bombers which were able to overcome anti-aircraft defences because it was hard to see them coming (p. 18). Similarly, art therapy was seen by veterans as a process which could get past the psychological defences that they felt they could not lay down of their own accord.

The section on British armed forces describes a world that is unfamiliar to me, so is useful orientation to the context in which Combat Stress operates. It is heartening to read about the positive efforts to provide mental health services. There are also interesting insights into the factors that make it difficult for military veterans to admit to problems – the control, hierarchy, self-sufficiency and macho culture (work hard, play hard, usually with alcohol) – which make it difficult to ask for help, and is seen as weakness. The chapter on ‘Coming Home’ outlines the way whole families are affected, and includes stories from veterans’ wives.

The third section, on approaches to art therapy, is the largest and the one most relevant to art therapists. It outlines the Combat Stress model of art therapy, which sees art therapy as achieving the best results when used alongside other treatments, especially Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR), Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) and Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT). This combination is seen as particularly relevant to PTSD, in which intrusive emotional memories need to be brought to light and then stored in a more cognitive way using CBT. The use of CFT is also seen as helpful for veterans likely to berate themselves for having problems.

One of the most interesting chapters for art therapists is the art therapy team’s description of the adaptive art therapy model they have developed. They quote (p. 107) NICE guidelines (2005) which recommend that non-directive therapy ‘should not routinely be offered to people who present with chronic PTSD’. So, the Combat Stress model is built around the three phases of recovery programme outlined by Herman (1992): (1) Establishing safety, (2) Remembrance and mourning, (3) Reconnecting with life. The team has found that a theme-based approach is safer for veterans, with certain themes particularly useful at each stage. There is a helpful list to illustrate this (p. 110).

There is a very useful chapter on research and evaluation, including a literature review, following on from Alison Smith’s literature review in IJAT 2016. This chapter also outlines research and evaluation conducted by Combat Stress itself – one survey on barriers to engagement in art therapy, and another one evaluating veterans’ experiences of the art therapy group. This showed the importance of art therapy in helping to access and express difficult feelings, for those veterans who cannot engage in verbal therapy. However, there is still a need for further research to identify the particular contribution of art therapy for veterans (Smith 2016), as the standard treatments for veterans are multi-modal programmes. I would have liked to see some suggestions as to how this might be achieved without short-changing veterans in their treatments.

The final section of the book ‘Taking a wider perspective’ describes several innovative collaborations with art institutions, such as workshops at Tate Modern and other art galleries; and exhibitions of work, both art and art therapy (to increase public awareness). These are part of the Combat Stress model, which values the contribution of art alongside art therapy – indeed, some veterans go on to study art after their treatment.

Their ground-breaking ‘Combat Art Project’ provided basic art kits to 500 Royal Marines deployed to Afghanistan in 2013, with the aim of providing an outlet for serving soldiers, which might help prevent the onset of PTSD later. The art works were subsequently collected and exhibited. Although intentionally not art therapy as such, this project highlighted the importance of creativity in maintaining mental health. The final chapter looks at the contribution of art to developing resilience and possibly even post-traumatic growth.

The book is illustrated by many drawings, and some wonderful colour plates, emphasizing the creativity of a section of society not normally involved in art. It’s a very encouraging book as it shows very clearly the contribution of art and art therapy for this specialised group of people who do not normally feature in therapeutic discourse.

But this book is not only for those working with veterans – we are beginning to recognise that many other groups may be suffering from PTSD – survivors of child abuse, refugees, accident survivors, aid workers, to name but a few. Therapists working with many client groups would benefit from reading this book and putting its ideas into practice. I hope this interesting book will be widely read.

References

Herman, J. (1992) Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence from domestic abuse to political terror. New York, NY: Basic Books.

NICE (2005) Post-traumatic Stress Disorder:Management. Retrieved from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg26/chapter/1-Guidance. These have been replaced by NICE guidelines (2008) NICE Guidelines NG 116 Post-traumatic Stress Disorder: Guidance & Recommendations. Retrieved 28.3.20 from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng116 These guidelines recommend EMDR and CBT, and make no mention of non-directive therapy.

Smith, A. (2016) ‘A literature review of the therapeutic mechanisms of art therapy for veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder’ in International Journal of Art Therapy: Inscape, Journal of The British Association of Art Therapists, Volume 21 Issue 2 July 2016.

Copyright (c) The British Association of Art Therapists (BAAT)

This article is published in BAAT Newsbriefing Summer 2020 and may not be distributed or published without the consent of BAAT