As COVID-19 commenced its spread across the UK in March 2020, school closures suddenly became inevitable. Art Therapists were faced with the dilemma of pausing / ceasing therapy with their clients for an uncertain but potentially lengthy amount of time, or attempting sessions remotely as the nation adhered to Government ‘Stay at Home’ guidelines. As two therapists working in schools – Mary in mainstream primary in Greater Manchester, and Amy in a Special Educational Needs (SEN) setting in Birmingham with 4-19 year olds – neither of us wanted to bring anyone’s therapeutic journey to a sudden and premature end; however, there were many issues to overcome when considering online sessions at home. The abrupt nature of the huge life changes the nation was about to face gave little time for deliberation and we chose to attempt remote sessions to, at the very least, provide continuity and bridge the gap before ‘regular’ face-to-face therapy could recommence.

Preconceived ideas about remote art therapy

Before this pandemic, neither of us had considered remote art therapy as an option with our client groups for the following reasons:

- The inconsistent space and difficulty of ensuring a confidential and nurturing environment

- Potential distractions in the home environment that could not be controlled

- The complications of containing any mess made in the child’s home setting

- Communication limitations including difficulties seeing body language or the child’s art making

- Possible challenges with technologies involved

- The lack of safety and privacy of the child’s artwork and materials

- The inability to help the child if they needed it

- The extent to which some children would be able to focus on a restricted video set-up

We questioned whether the children’s engagement and usual enthusiasm for art therapy would wane. Some may struggle to find a quiet space; some may find the video format awkward; or would prefer to be playing in the garden with siblings on sunnier days. We were fully prepared for these obstacles to complicate remote work and, at best, expected sessions to feel somewhere in between a holding session and a regular face-to-face session.

Under these exceptional circumstances, we both rapidly opened up to the idea of remote working. Ultimately we wanted to avoid a sudden pause or cease of therapy, particularly when considering some children (many with autism) who struggle enormously with change, or those who are looked after and could feel particularly abandoned owing to their history. Those children with trauma histories were also at heightened risk of having traumatic feelings resurfaced or exacerbated. We hoped that continued art therapy sessions could provide children with a glimpse of structure and predictability, and they could feel a little more ‘held’ and secure versus overwhelmed and dysregulated.

As self-employed Art Therapists working with small school pastoral teams, it was clear that we would need additional clinical supervision, and to closely monitor any guidance from BAAT and similar professional bodies when arranging sessions in this new format. There were multiple obstacles to overcome to ensure that our practice was as safe and as therapeutic as possible, whilst optimising engagement.

Setting the scene for a new way of working

The context

The atmosphere in schools in the two weeks before their closure was one of shock, uncertainty and chaos. Many schools had multiple staff and pupils already absent with potential COVID-19 symptoms, or needing to isolate. Class numbers dropped daily as panic rose amongst parents and staff who questioned whether schools should be open. Children worried that they had the virus, staff and parents were concerned about their health and loved ones in high risk groups, and about job and financial security. We were mindful that, while the community around us was operating in survival mode, we were not immune to these pressures in our own lives. In Amy’s case, her own personal situation additionally caused a sudden realisation of the need to stringently socially isolate before the official school closures.

The world as we knew it was changing quickly and no one seemed untouched. Amongst the challenges of the situation and a very short window of time to make such big decisions about our practice, there was a need for deep reflection. We tried to keep the child’s wellbeing at the centre of our decision making.

Preparation with the team around the child

Head Teachers were positive and supportive of us continuing our art therapy sessions remotely. Most children also welcomed the idea, some excited and relieved. Two older children in mainstream preferred to pause their therapy as they felt uncomfortable about doing sessions online or via any other remote option offered. One of these agreed on regular ‘check-ins’ with a parent; the other insisted he would be fine until school reopened.

We then contacted parents and carers to discuss the practicalities of remote sessions. They were unanimously positive about the prospect of continued support. Like all of us, they were processing the dramatic events, and worried about the impact of the situation on their children. Being open about remote sessions being new territory for us all, not claiming to be experts in therapy amid pandemics, and being clear that we would continually review the value of the work, seemed to allow for a new level of connection with parents. Parallel to this, there was a great level of compassion emerging, and an understanding that everyone involved was experiencing some level of fear and chaos.

The logistics and reality of remote sessions

Technology

In the first weeks of the pandemic, online safety, Wifi signal, and the client’s familiarity with technology, quickly became important considerations in our practice. There was much debate about which software offered the best security for online therapy, yet alongside this was a level of mistrust from some families owing to the unfamiliarity of some platforms. Some weren’t as ‘tech-savy’ and found the suggestion of using new apps overwhelming. In a few cases, phone sessions were arranged instead, in others, video-conferencing apps Zoom and Skype were used, or peer-to-peer direct messaging services that families were more familiar with. These were accessed via laptops, tablets and phones, usually hosted on the parent/carer's account. We had to remind each child that we simply couldn’t guarantee the same level of confidentiality as we can in face-to-face sessions.

The physical setting

As therapists, the absence of a physical space that we could cultivate to feel safe and nurturing for our clients, was an alien concept. We carefully considered the set-up of our own spaces to provide a quiet, calming and neutral backdrop, without distractions, that the children would see on their screens and come to consider as their art therapy room.

On the other side of the screen, the child and their parent/carer, now shared responsibility for creating a suitable space. This wasn’t always possible. Kitchens, lounges and bedrooms became the other half of our art therapy room.

Some caregivers became trusted assistants in helping set out materials in front of their device before exiting the room. Younger mainstream children naturally used their grown-ups if they needed help with cutting or cleaning spillages by temporarily leaving the room, or quickly inviting a parent in. This was far from our normal way of working; however, it felt important to be flexible and to allow the child to ask for help. In the SEN setting, this was less of a factor, yet when the sessions finished, parents were typically invited in to witness the child’s creations.

The roles that both the child and caregiver adopted in setting up the materials, taking care of artwork, and the responsibility they had as ‘shared guardians’ of their half of the space was particularly interesting to observe. The caregiver has had real power in supporting or hindering the quality of the therapy. In cases where they were more active, this seemed to strengthen relationships.

Some children clearly enjoyed inviting us into their homes, introducing us to siblings, pets, and different rooms in their houses, giving us more insight into each of their lives. They usually took pride and responsibility for their half of the space which appeared to empower them; however, we were mindful of the extent to which this, and our physical absence, limited the child’s ability to externalise their feelings with any mess that we would normally help to contain. In fact, some that had been making mess in the school’s art therapy room before lockdown, naturally reined this in at home. The absence of mess has been one notable limitation of remote working.

It was fascinating to observe that, in cases where we were not confident that video sessions would work, many pupils thrived. A couple of younger children in particular were able to focus notably better with just the screen and the art as their reference points when typically they would move around the art therapy room, distracted by different elements of the space. Now, instead of releasing their energy in a more physical way, they seemed to channel it into their art or their communication with us via the screen.

With some pupils in the SEN setting, a noisy classmate in the corridor or an unexpected balloon would send them into a frenzy and require time to calm them down. For these children, many with autism, the home environment was quieter and more predictable. While some were more open and engaged, others were fearful of this new experience; especially complicated when a screen was inaccessible and phone calls limited the level of comfort and support that could be provided.

Privacy and confidentiality

It was inevitable that a confidential space at home would not always be possible. We were unable to control interruptions or people overhearing/seeing artwork. Nor could we totally mitigate the risks of ‘hosting’ sessions via virtual software. Initially, this felt unnerving. However, the risks were outweighed by the benefits of continuing therapy.

In their first week or two, the children seemed more aware of their reduced privacy; many would spend time looking towards the door seemingly wondering who might be there. At times a loud sibling would run past, or limitations on space at home would impact confidentiality. In these cases, sessions would naturally develop into lighter ‘check-ins’. Using our intuition and sensitivity in each individual situation to gauge this was a must. Some children would take a more active role than others in protecting their privacy. At times, parents were abruptly corrected by their angry teenager to “get out”, followed by a quick apology and escape.

We made a point of acknowledging the strangeness and difference from our school set-up with the children. They quickly seemed to relax and adapt to this new, less secure, set-up, as simultaneously we attempted to do in our daily lives in the context of the pandemic. Many children instinctively went back to their art making and kept this as their focus, as though it was their safe base.

Art materials

Time did not allow us to create packs of art materials for all the children across the different settings. Where we were able to, this was seen as a way to encourage engagement and help children feel cared for in this unsettling time, especially with those who didn’t have access to many materials at home. The quantity and quality of materials was considered, as well as the type of material that each child might be drawn to.

For those without pre-made packs, and where they did have access to some materials, it felt rather organic for pupils to select and gather what was available to them. This served to demonstrate what pupils themselves felt was imperative to their process.

Handing the responsibility to the child of caring for their materials and artwork, noting that these couldn’t be kept safe in our locked cupboard as usual, largely seemed to excite them. Many enjoyed the idea of finding their own storage space and spoke about secret cubbyholes, safe from sibling hands. Most children took much more care than usual in tidying up their materials and artwork, reflecting their enjoyment of this new responsibility.

Art making and the therapeutic process

All of the children we worked with remotely had been in therapy for several weeks, so trust was largely established and we had already voiced the reason for their referral, some in more depth than others depending on their level of understanding and the direction their therapeutic process had taken. This established relationship before ‘going remote’ felt paramount in ensuring the continuation of meaningful work over these weeks. When the Wifi signal let us down, or when there were concerns about a family member overhearing them, we weren’t solely reliant on words, and could hone in on the art, exploring their feelings indirectly through this. The art sometimes felt like our secret language while we were trying to maintain the confidentiality of our face-to-face sessions. One child with autism wrote messages on their iPad, almost poetically describing feelings, a confidential and silent dialogue that they chose to lock away with a code. This was a precursor to sharing thoughts with a parent that they had kept locked up in the past.

Despite other difficulties in the children’s lives, or past circumstances that brought them to therapy, the feelings and issues that emerged over this period revolved largely around the impact of the current pandemic. Overall, the children just wanted to be heard and witnessed, and most made good use of the space to make sense of their feelings.

We sometimes struggled to see a great deal of the creative process via the screen, and undoubtedly a lot of non-verbal communication was lost. Despite this, we were still able to gauge a lot about the child’s state of mind from the physicality of the application of materials; glimpses at their choice of materials; or the amount of time they spent sitting or standing.

At times, there was a heightened sense of communication via the noise of the mark making as devices picked up the sounds while resting next to the image on the table. The intensity of the sound was amplified and brought into focus for both the child and therapist. This heightened our awareness of the motion of their movements and clearly displayed the child's frustrations along with the relaxation that followed. One girl with autism explored listening together, encouraging a dialogue about whether she was drawing a straight line or a curve, repeating her marks until the correct answer was reached. This extra focus helped the relationship feel strong and intuitive despite this new setting.

We made the children aware of what we could and could not see, hear and not hear, and in many cases, we became more reliant on the child’s description of their art making, offering both child and therapist a deeper understanding of their experience, in the child’s own words. Many children were proud of their creations as they held them up to the camera, seeing the screen’s ‘framed’ images reflected back at them.

One pupil with autism who usually sticks to one colour palette in school, extended to an array of colours, perhaps feeling braver at home, or perhaps influenced by the collective symbol of the rainbow that we see in windows across the country. Another who typically painted loosely and freely in school, started telling stories as they created.

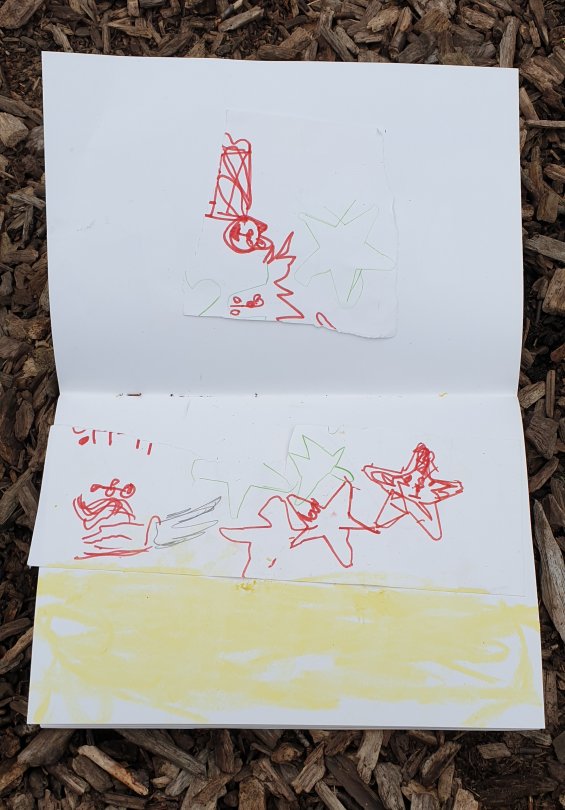

With both therapists using a non-directive psychodynamic approach, it was interesting to observe similar themes in the children’s images. At the start of the pandemic, multiple pictures of boats appeared (one in shark-infested water, another made from a ripped piece of paper and coloured as if it were a patchwork). In the first week of school closures, one child asked to do joint art making, specifically requesting that we close our eyes as we drew our own boats, finishing off with our eyes open (see above). This felt symbolic as we were both doing our best to navigate our way through uncharted waters during the pandemic, the art helping to guide us.

As the weeks progressed, metaphorical stories appeared with threatening characters – animals that could kill with a sting or bite, or scary ogres or wizards with deadly poisons. One child drew two imprisoned ‘goodies’, both of whom were trying to stop a deadly poison from being given to innocent people. All of these images provided opportunities to explore feelings of looming danger; fears about the safety of loved ones; confusion and frustration at having to stay home; missing school, grandparents, friends; and the difficulty of not being able to plan and predict the future. Stories of fear, sadness and injustice were common. In some cases, especially in the SEN arena, children needed to make sense of the ambivalence of both enjoying being at home whilst worrying about loved ones potentially catching the virus and dying.

One child made a drawing of a stinging starfish and later cut up the image then, in our final session, stuck it back together and added a beach added.

Storytelling became more apparent than usual, possibly a consequence of feeling less inhibited when at times they forgot we were on the other side of the screen. Some children, seemingly relieved to be able to explore worries they had been harbouring, created positive endings, making themselves the saviour of their story, allowing them to feel empowered, a feeling which they were able to hold onto after image making. Others, whose set-up felt more private, were able to verbalise feelings that had resurfaced owing to the pandemic, triggering memories where they had experienced significant fear or loss. They were relieved to tell their stories.

Conclusion

Still in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic as we write this, the experience of remote art therapy has been overwhelmingly positive as a way of continuing each child’s therapeutic journey amid social isolation. The reality of video sessions was very different to our initial expectations. Most of the children have appreciated the consistency and structure that these have provided and many have thrived in this new way of working, attending sessions in an engaged and grounded manner.

We appreciate that remote art therapy is not feasible in all cases, and some will have paused or ended therapy with their clients. As self-employed Art Therapists, we both reflected that we would apply caution to working remotely with certain clients.

The absence of a secure physical space which felt sufficiently confidential, nurturing and containing, undoubtedly hindered the process of some children, whilst for others it did not appear to be much of a factor. However, the experience has served as an acute reminder of the power of a trusting therapeutic relationship and a strong internal setting in enabling the child to continue their process.

While we have delighted in seeing the children adapt from week to week, this way of working has not been without stress. The chaos in the lives of some families meant that session times did not always run smoothly; reminders have been needed; calls at scheduled session times sometimes went unanswered. In unsettling times, more energy and a higher degree of flexibility was needed to ensure sessions could take place.

Speaking to parents sometimes before and after sessions would not usually be a component of our practice at school. It took another level of discipline to continually reiterate the boundaries of confidentiality here. Caregivers also offloaded at times, and therefore working days often felt heavier and more exhausting. It became clear that self-care in times of collective trauma and uncertainty was more important than ever.

The COVID-19 pandemic hurled us out of our comfort zones and forced us to quickly adapt and evolve as a profession. This article provides just a few snapshots of the most impacted aspects of our remote experience as we continue to learn, reflect and monitor our work. Remote art therapy could evolve to be incredibly beneficial in the future, as it has shown to be now, particularly for isolated client groups. For children who have thrived in this way of working, or for some autistic clients for whom social isolation has been more settling, adapting to a 'new normal' back at school may be particularly difficult and heightened support may well be needed post lockdown.

The experience of taking our practice online has been one of learning and professional growth. It has been fascinating to compare experiences and observe emerging themes in the wonderfully rich artwork that has been produced. We are eager to explore this in more depth, as well as the plethora of questions that our experiences have sparked.

Such dramatic changes to our practice will undoubtedly continue as any face-to-face art therapy resumes amid the COVID-19 pandemic. We will continue to have much to reflect on, explore, and learn and we hope that this article can, to a degree, serve as a compass as we navigate this new territory.

Copyright (c) The British Association of Art Therapists (BAAT)

This article is published in BAAT Newsbriefing Summer 2020 and may not be distributed or published without the consent of BAAT